The Quiet Power of the Marginal Note

In an age of digital highlights and algorithmic summaries, the physical margin of a book remains a uniquely intimate space. It is a territory of private conversation, a site where reading slows to the pace of thought. The marginal note—whether a scribbled question, a vehement underline, or a simple exclamation mark—transforms the act of consumption into one of dialogue. This essay considers the marginalia not as a defacement, but as a vital form of cultural annotation and personal archaeology.

The history of the margin is rich with clandestine voices. Medieval monks filled the borders of manuscripts with complaints about the cold, sketches of beasts, and theological quibbles. Renaissance humanists argued with classical authors in the white space surrounding the text. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s copious annotations in borrowed books became so famous they were published separately. These marks are more than commentary; they are a record of the mind in friction with another mind across time.

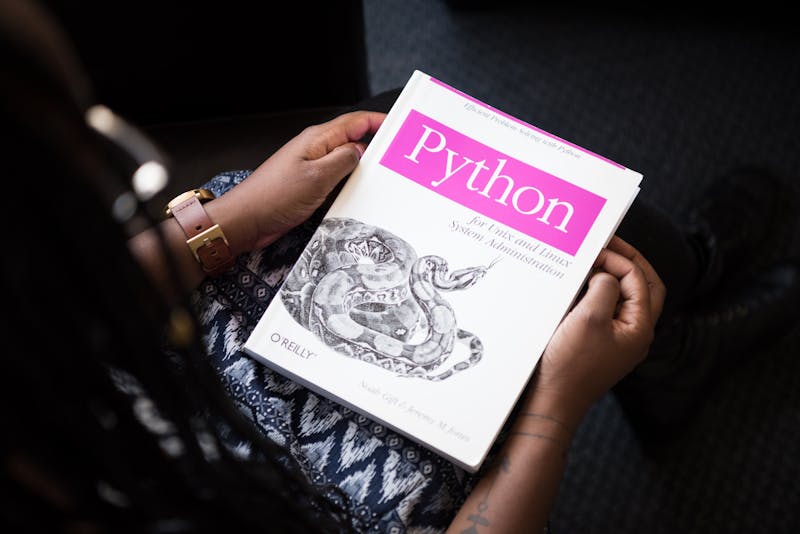

What cultural function does this private act serve? Firstly, it resists the passivity of streamlined digital consumption. To annotate is to engage, to dissent, to agree vigorously. It creates a palimpsest where the original text and the reader's response coexist. This layered document becomes a new artifact, one that future readers—perhaps the annotator's future self, or a stranger in a second-hand bookshop—can discover and interpret anew.

Secondly, marginalia operates as a form of curation. In a world of information overload, the act of underlining a sentence is a primitive but powerful filter. It says: This matters. Remember this. A shelf of annotated books becomes a personalized index of one's intellectual journey, a map of influences and evolving ideas far more nuanced than any digital "likes" or "saves."

"The margin is the reader's studio, a workshop for half-formed thoughts that may one day become essays, stories, or simply a better understanding."

Yet, the practice is threatened. E-readers and subscription services often render annotation ephemeral, locked to a platform or an account. The physical book, with its permanent margins, offers a kind of democratic permanence. The note you write today might be puzzled over by your grandchild, or by a random reader fifty years from now, creating a fragile, human connection outside of official channels of publication.

In conclusion, the cultural significance of the marginal note lies in its affirmation of the reader as a co-creator. It is a small, persistent act of resistance against the monolithic authority of the published text. It reclaims reading as a participatory, messy, and deeply human endeavor. To preserve the space for marginalia—in our habits and in our tools—is to preserve a vital channel for critical thought and personal reflection within our literary culture.